- Home

- Ruth Tenzer Feldman

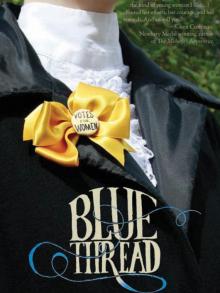

Blue Thread

Blue Thread Read online

Blue Thread

RUTH TENZER FELDMAN

© 2012 by Ruth Tenzer Feldman

All rights reserved.

ISBN13: 978-1-932010-43-5

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Ooligan Press

Department of English

Portland State University

P.O. Box 751

Portland, OR 97207-0751

www.ooliganpress.pdx.edu

Interior design: Brandon Freels

Cover design: Kelsey Klockenteger

Title design: Matthew Wilson

Author Photo: Colleen Cahill

Set in Adobe Caslon Pro and Franklin Gothic Book.

Photo on page 294 courtesy of the State Historical Society of Iowa

Images on page 297 courtesy of the University of Oregon Libraries

Printed in the United States of America.

For additional educational materials, see our website.

DEDICATION

For Anna Bertha Koritansky Tenzer, my “Nana,”

who introduced me to boiled chicken feet and a wider world.

EPIGRAPH

People like us, who believe in physics,

know that the distinction between past, present, and future

is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.

—Albert Einstein

Well-behaved women seldom make history.

—Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

PROLOGUE

The unforgiving sun sparks and flashes against the deadly edge of a raised spear. The desert air hums with the hisses and curses of my kinsmen. Miriam calls to me in a language that only I can understand.

“Serakh, I need your power to speak to him.”

I struggle in vain against the men who keep me from Miriam’s side. “I do not have such power to give you,” I shout over the noise. “Come away. Now!”

She does not answer. I raise my voice once more, this time to the one man who can save her. I use the ancient language that is his mother tongue and mine.

“Miriam pleads on behalf of Tirtzah and her sisters,” I explain: “She pleads for all daughters who seek a better life. I have brought her here. She is a messenger who deserves respect, not punishment.”

He says nothing. He does not look in my direction. Could it be that he has not heard? He turns his eyes to Miriam and strokes his beard, frowning.

I beseech her again, “Come away, Miriam.”

But she does not.

I turn my face toward the heavens, close my eyes, and pray—for all of us.

May Miriam’s spirit remain unbroken.

May she find strength in the blue thread that unites us.

And may it be Your will that our people allow her to live.

CHAPTER ONE

Portland, Oregon

Friday, September 20, 1912

“You should not have encouraged them, Miriam,” Mama said, once again dividing my life into her shoulds and should nots.

I touched the bright yellow VOTES FOR WOMEN bow Charity had pinned to my navy jacket, and I looked back at the small shop with its hand-lettered sign: Osborne Milliners. Then I flung one of Mama’s favorite mottos at her: “It pays to be polite.”

With no school and Florrie away, Portland was lonely. I didn’t bother to explain that Charity Osborne had friendship potential. Charity and her sister Prudence were practically my age. All I did was smile and offer to help them get settled. It was Mama who admired their fancy hats.

“I have no notion where the Osbornes come from,” Mama countered. “But in Portland, women expect milliners to sell millinery and not lecture their customers about suffrage.”

“They come from Chicago. They’re businesswomen.” I liked the way businesswomen rolled around in my mouth. Mama reached for my elbow to cross the street. Linking arms between one curb and another goes in her should category for proper young ladies. I stepped away and skirted a batch of horse droppings baking on the cobblestones. Once we made it to the other side, Mama shot me a disapproving frown. She tucked one of her blonde curls into a hat as fussy as a Rose Festival float.

“Businesswomen? I’d call them spinsters. You would think there were enough bachelors in Chicago to go around. They needn’t have bothered with Portland.”

Her remark wasn’t worth answering. I retied the ribbon that tamed my unruly brown frizz, then smoothed my gloves.

Mama fixed her eyes on Charity’s bow. “I’ll thank you not to aggravate your father when we get home for dinner. You know how much he enjoys a relaxed meal.”

And I don’t? I thought. Still, I buried the bow in my jacket pocket, lest Papa see it. Why spoil my last meal before our Yom Kippur fast? I commenced to hum, which Mama regards as most unladylike—definitely in her should not category. She pursed her lips all the way to our front door.

***

At dinner, Mama entertained Papa with the tale of our maiden voyage to Osborne Milliners—and nary a whisper about Charity and Prudence’s efforts to win voting rights for Oregon women come November. Naturally.

“Hilda Steinbacher says she plans to wear an Osborne chapeau to temple tonight,” Mama said. Chapeau—as if “hat” wasn’t fancy enough for the dinner table, as if French instantly turned chatter into conversation. Papa dabbed his mustache with a corner of his napkin. He gave her The Adoring Look, as usual. They eyed each other as if I weren’t even there. I took an extra dollop of whipped cream and savored my last bite of peach cobbler.

Two hours later, we crowded into a pew at Temple Beth Israel for the Yom Kippur evening service. I smoothed the narrow brim of my simple navy hat and searched the congregation. Mrs. Steinbacher was easy to spot, owing to an eruption of ostrich plumes and felted roses spewing from her head. Florrie would have been appalled by her mother’s hat. Surely Charity hadn’t created that monstrosity. It must have been Prudence. I settled into my seat and prepared for boredom. Then I noticed the temple’s new prayer books. I picked one up and opened it eagerly.

What a wonder! I thought. White space and text covered each page in perfect proportion. English words printed from left to right balanced Hebrew words printed from right to left. Tiny dots and dashes straddled the Hebrew with exquisite precision. And the typefaces—inspirational. I might only be a printer’s daughter now, but one day soon I’d be a printer as well.

Rabbi Wise prayed for peace, justice, and mercy. He urged us to vow that we would be better people in the coming year. I vowed to improve my typesetting skills.

After services, I told Mrs. Steinbacher her holiday suit looked lovely. I didn’t mention the hat.

“We so miss our Florrie, don’t we, dear?” she asked, as she waved to another of Mama’s friends in the congregation.

“I can’t wait for her to come home for Thanksgiving,” I said, looking around for anyone I might really want to talk to. I noticed an odd-looking girl who stood by the front door. Not odd as in scary. Odd as in intriguing. The girl’s bronze-colored skin reminded me of the brown and gold pigments Papa added to the printer’s inks that he never let me touch. She looked about my age, yet the thick braid that fell to her waist was old-woman white. No hat, no hair ribbons. Her plain gray dress was a size too small, several years out of fashion, and missing a button. She certainly hadn’t come to flaunt her finery. It’s possible she had come to pray.

I smiled at the girl as Mama, Papa, and I walked toward her. She glanced at me, and for a moment it looked as though she wanted us to meet. Something about her made the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Then she shifted her gaze to Papa, w

ho had stopped to talk to Mr. Steinbacher. Her face seemed to harden. She turned away and folded into the crowd.

I kept thinking about the strange girl during the ride home. From the back seat of our Oldsmobile, I saw a sign on the Orpheum Theatre advertising a vaudeville show featuring ragtime piano. Perhaps she was a performer—there were plenty of Jews in vaudeville. I dubbed her Fantastical Fannie from Frisco and began designing a handbill in my head. Once we were back home, I went up to my room and put the design on paper. I copied ideas from the typographer’s Bible: The Art & Practice of Typography: A Manual of American Printing by Edmund G. Gress. My design was mediocre. To be honest, it bordered on wretched.

Frowning, I rubbed my aching shoulders. Dispirited, I turned to the front of the book, and read aloud:

To the typographer who,

seeking knowledge and inspired by ambition,

goes about his work with a stout heart and sensitive conscience,

succeeding in spite of every discouragement, this book is dedicated.

Papa was my main discouragement. I erased half of Fantastical Fannie’s handbill and started again. By midnight, my design bordered on professional.

I went to bed feeling proud of my efforts, but awoke knowing I was doomed to a full day of Yom Kippur services on an empty stomach. We rarely went to services—we hadn’t even gone to Rosh Hashanah services earlier in the month to celebrate the Jewish New Year. But Papa always insisted that we observe every minute—sundown to sundown—of the Day of Atonement.

***

By early afternoon I had lost interest in the new prayer book. The congregation droned. The rabbi exhorted. The cantor sounded like a one-man opera. I counted twenty-four ringlets on the little girl sitting to my left and breathed in the spicy pomade of the man in the next pew. I listened to the organist pound out majestic melodies, and I watched daylight inch across the stained glass windows. Sundown was taking forever.

But when I turned to page 291, the prayer book once again caught my attention. I stared in adoration at the capital M in “Memorial Service.” Its apex had a concave dip, so the top of the letter seemed to be smiling. The left foot serif was angular and the right one curved, like oddly matched shoes. Fanciful yet solid, that M was an answer to a typographer’s prayer.

“Miriam, we are reading responsively on page 294,” Papa said, as if I were six and not sixteen. Color rose in Mama’s cheeks. She coughed quietly, and I turned to the correct page in my prayer book.

After the final “amen,” Papa slid his prayer shawl from his shoulders and tucked it inside its black velvet bag. When Mama started a conversation with the woman behind us, I escaped to the social hall downstairs and broke my fast with a deviled egg.

I heard a shuffling noise behind me, turned, and almost choked on my food.

There she was again, that odd girl, wearing the same gray dress and stuffing cucumber sandwiches into a large handbag. Who was she? I hadn’t seen someone so exotic since my friend Florrie and I snuck into the fortune-teller’s tent at the Lewis and Clark Exposition when we were nine years old.

The girl looked up and caught me staring. She nodded and made her way closer. Barely managing to swallow the egg, I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Maybe she was from Persia or Afghanistan. She looked like she belonged in National Geographic Magazine. When she reached me, she touched my arm.

In an instant, I forgot how hungry and tired I was.

Her eyes were hazel, like mine, but flecked with gold. Her eyebrows and eyelashes were as white as her braid and looked as mismatched with her young skin as italics in a block of Roman capitals. She was thin, like me, but a head shorter, and she exuded a faint odor of farm animals. Goats?

“These eggs are delicious,” I said, hoping to engage her in conversation.

“I have a passion for cucumbers,” she said. Her voice was deep and strong, and her accent was slightly guttural like Papa’s, but different from his familiar German accent.

“I have come a long way for you, Miryam,” she said, staring straight into my eyes.

How did she know my name? Maybe Fantastical Fannie was a new student at my old school, and they told her to meet me at services. How many tall Jewish girls with brown frizz and hazel eyes could there be in Portland? Three?

I extended my hand. “It’s Mi-ri-am, not Mir-yam. Miriam Josefsohn. Pleased to meet you.”

“Mi-ri-am.” She said my name slowly, as if struggling to get it right. I stood there, not wanting her to leave, not knowing what else to say. She devoured her sandwich and resumed speaking as if there were no awkwardness between us.

“Where are your tzitzit?”

“Excuse me?”

She frowned. “Tzi-tzit,” she repeated. “Fringes. The garment of fringes.”

“Do you mean my father’s prayer shawl?”

She shook her head. “The fringes that belong to you.”

I pictured everything in my armoire. “I do have a silk shawl that belonged to my grandmother. It has tassels at the corners.”

“Tassels? Yes, perhaps you call them tassels. Is there a single thread of blue?”

“Not as I recall.”

“This blue thread you would remember. You must have this garment.” She squeezed my arm and stepped even closer. “Do your elders deny you your fringes?”

I frowned at the bronze hand crushing my sleeve.

She released me and stepped away. “A thousand pardons,” she said. “Come with me. We must talk.” When I paused to collect my thoughts, she held out her hand. Her fingernails were short and her skin calloused. “Please come, Mi-ri-am. I have something to show you. Let us meet outside.”

I cradled another deviled egg in a paper doily and watched the girl wobble up the steps in old-fashioned, ill-fitting shoes. I hardly knew her. Unease grew in the back of my mind.

She slipped once and grabbed the banister, looking like a child in her mother’s shoes.

I decided to follow. If need be, I could outrun her.

CHAPTER TWO

The corner of Twelfth and Main was quiet, despite the nearby streetcar lines. The sun touched the West Hills, and the warm evening air smelled of late-blooming roses. I nibbled my egg. The odd-looking girl picked cucumbers from another sandwich and showed me the spread slathered across a slice of crustless rye.

“Curds?” she asked, looking at me with wide, gold-flecked eyes.

“Cream cheese, Miss…um…” She didn’t take the hint. “Excuse me, but I didn’t catch your name.”

She laughed. “I did not throw it to you. Call me Serakh.” It sounded like “Sarah” with a gagging noise at the end.

“Serakh,” I repeated, trying to get it right. I searched for a topic with which to make polite conversation as she chewed her sandwich. “After services last night you seemed to recognize my father. Do you know him?”

She chewed on a cucumber, ignoring my question. “You must tell no one that we have met, not even your mother and father. They would only pester you with questions.” Then she reached into her handbag and handed me something flat and thin wrapped in waxed paper.

“See for yourself. Tirtzah and her sisters have been remembered.”

Inside was an old newspaper article. The headline read:

SUFFRAGISTS PARADE STREETS

HUNDREDS IN LINE THIS NOON LED BY MISS SHAW.

I glanced at the first paragraphs, which contained nothing about a Tirtzah. “I’m sorry, I don’t understand. Are Tirtzah and her sisters members of the congregation?”

Her eyes sparkled. “The same tribe, yes. Tirtzah needs you, Miriam. You must find your fringes. Now go in peace.” She walked away, leaving the article in my hands.

“Wait!” I lifted my skirt and petticoat and followed her.

She looked back, her white braid snaking over her shoulder. “I will return when you have your tzitzit. You must find them or I have traveled in vain. Do not follow me, Miriam. When we meet again, I pray you will come with me, for the sake of our people.”

Our people? I didn’t race after her, even though I wanted to. Serakh seemed to expect obedience—like Papa, only nicer. I watched her disappear around the corner, and then I slipped the article into my handbag and returned reluctantly to the social hall. Keeping my encounter with Serakh to myself, I asked my parents if they had heard of a girl named Tirtzah.

Papa rubbed his chin. “No, I do not know this person. Lillian?”

Mama shook her head. “Why do you ask?”

I pretended to brush a crumb from my suit jacket. With Mama I thought it better to volunteer a half-truth than to be forced into the entire truth or an utter falsehood.

“Oh, I heard the name today and wondered where it comes from.”

“Curiosity killed the cat,” she said—another of her favorite mottos. “You should avoid what isn’t your business, Miriam.” My parents wouldn’t comprehend curiosity if they saw it printed in seventy-two-point Franklin Gothic.

I held my tongue and said nothing more.

***

Uncle Hermann and my little cousin Albert were eating appetizers in the parlor when we arrived home.

“Lillian, my dear, I am delighted to see you.” Uncle Hermann smoothed his mustache and kissed Mama’s hand. He ignored Papa, but smiled at me and gave me a quick embrace.

I happily returned the smile and the hug. Uncle Hermann was so much easier to get along with than Papa. “How are Aunt Sophie and the baby?” I asked.

“Resting nicely,” Uncle Hermann replied. “She’s sorry she couldn’t come to dinner.”

Papa eyed Albert, who was busy extricating an unsightly yellow glob from his ear.

“Soon you must share your toys like I had to when your papa Hermann was born. Now we share a printing business,” he said, reaching into his breast pocket.

“I won’t share my tin soldiers,” Albert said, ignoring Papa’s proffered handkerchief. “Or my rock collection. The baby can find his own rocks.”

I looked at Mama. She had that familiar sadness in her eyes—The Danny Look. I hugged myself, feeling the ache of loss in my own chest. How many of those tin soldiers had been Danny’s before Albert claimed them?

The Ninth Day

The Ninth Day Blue Thread

Blue Thread